THE NIGHT I DIED

There’s no graceful way into this. So I’ll just say it. One way or another, I’m pretty sure I died on the night of my fiftieth birthday.

I wonder which part of that people will find harder to accept, my claim to have died, or to have been fifty when it happened? Either way, you’d better brace yourselves for worse. Things just get even weirder from here.

Of course, it’s a damn strange ghost that everyone can see and touch and talk to. A ghost that has to eat and shit and piss and sleep—that dreams and sweats, and smells unless it bathes. So, not exactly dead perhaps. And not just dreaming either after all these years. But if not dead or dreaming, what am I?

I still have no idea.

All I can say for sure is that I was not at all what I seemed when I showed up on the Avenue. I’d been someone else entirely just weeks before.

I suppose I should say something about the man I’d been, though there seems so very little to recommend him.

His whole life until that night could be summed up in one short phrase: ‘well behaved.’ Unless you’ve personally experienced the misfortune of being well behaved for more than brief, healthy spurts, you can have no idea how sad that was.

He was generally liked, I suppose, if loved by no one he could have pointed to quickly—had he ever thought of trying to. He was dignified, content, and generally healthy, if never very charismatic or wildly happy. He had diligently worked his way into management at a small firm in the city. He owned a pleasant condo and a pleasant car—both kept clean and in perfect working order at all times. In short, he’d spent his life executing every move on any dance chart he’d encountered with modest precision and unquestioning confidence. Oddly though, until that night, he had managed somehow not to notice that he was also entirely alone, even though—or perhaps because—he’d been that way almost forever.

It still makes me wince to recall his meticulously unexamined existence. He imagined himself comfortable, respectable and secure. Exemplary, even.

He was that profoundly self-deceived.

I, I mean. I was that self-deceived. It’s cowardly to speak of him as someone else. His errors were mine. I am what has become of him.

It’s so clear to me now, of course, that my life then was more numb than comfortable—and anything but ‘secure.’ Fear and shame had always defined me, though I had no conscious understanding of that then—much less of why.

Among the countless things I feared then was my upcoming birthday. I think fifty had always been an unconscious sort of magic number for me—an irrevocable line in the sands of time, anticipated for so many years with such well-suppressed dread that when a much younger colleague named Brian congratulated me at work one day on “the happy milestone” I just blinked at him, wondering what important project deadline I’d forgotten, or worse yet, never even heard about.

Once my confusion had been remedied, Brian seemed horrified to hear I just planned to ignore my birthday entirely. “It’s not as if you’re turning ninety,” he said. “Fifty is—”

“Do not say ‘the new forty’,” I remember growling, as if it were a joke.

Brian shook his head, almost affectionately as I recall, insisting that he could not allow me to go home on such an occasion “to some microwave dinner and an episode of Survivor.” It still appalls me to think that my lifestyle was so readily apparent.

He said his wife and he were taking out a visiting friend that night, and pressed me to come along and let them buy me a nice birthday dinner. He assured me that their friend, Jessie, was a delightful, intelligent woman with a great sense of humor, and promised there’d be no embarrassing table-side sing-alongs, gifts, or surprise guests.

A less well-behaved man might just have said “No, thank you.” I said, “Shouldn’t you ask your wife about this first? And your friend? It seems an awful lot of trouble on such short notice.” None of which meant no to a well-intentioned youth like Brian.

By that evening, the plan had expanded to include an early movie before our meal. I had agreed to meet them at the theater, but a string of mishaps at work made me late, and the previews had started by the time I found Brian waiting just through the inside door to guide me down the darkened aisle to a seat beside their friend.

I could barely see her in the darkness, but Jessie’s palpably relaxed and welcoming demeanor put me instantly at ease. We exchanged whispered pleasantries during the last few trailers, and, within seconds, she had made me laugh. Within a few more seconds I had made her laugh in turn.

Even after the movie started, she kept leaning up to whisper droll observations about the film into my ear, so softly that I doubt even Brian or his wife could hear. I’d whisper some reply, and we would chuckle silently—our seats so close that I could feel the subtle trembling of her laughter.

Our instant rapport surprised me, and made me feel something I doubt I could have named then. But I can tell you now that it was ‘young.’ When I realized that the delightful scent tugging at my attention was her perfume, I wondered suddenly if Brian and his wife might actually have set me up with this friend of theirs on purpose—an absurd thought, all the more unsettling as I realized how little I would mind if it were true. To my quiet amazement, this was turning out to be a very pleasant birthday after all.

Then the movie ended, the lights came up, and my tidy little dirigible of denial crashed like the Hindenburg.

Beside me sat a lovely girl whom I was sure could not be more than nineteen years old. Oh, the humanity. I no longer recall a single specific thing Jessie or I said to each other that night, but I can tell you verbatim what my first thought was when I saw her in the light: “It’s years too late to meet this girl. Or any girl like her.”

I learned later that she was twenty-four. It was a birthday celebration. Ages were discussed. Mine was fifty. The five-year error in my estimate of Jessie’s age did nothing to suture the wound inflicted by this utterly un-looked-for ambush.

You may be thinking, ‘So he meets some pretty little thing who’s way too young for him. The world is full of them. Grow up, for heaven’s sake.’ And you’d be right if any of this had really been about Jessie. But it wasn’t. She was just the trigger, not the bullet.

A life forfeited as slowly and cautiously as mine had been leaves the forfeiter ample time to build walls around that loss, brick by mundane brick, day by unexamined day, so quietly that he need hardly know he’s building anything at all, much less what he’s walling out—or in. But oceans can accumulate behind such walls, until the slowly mounting pressure from one side becomes so great that any tiny crack is all it takes to bring them crashing down.

You must understand how long and carefully, if very unconsciously, I’d kept myself from anything or anyone that might have led to such a breach. Had I seen this woman for even seconds in the light before we shared those hours in the darkness, my heart’s smallest portals would have sealed instantly against her and all she represented, without so much as a whisper to alert me. I’d have been cordial all evening, even charming in a fatherly fashion, and gone home after dinner with no tiny clue that anything at all had been preempted. I’d been doing it for years. Who knows how long I might have kept it up before some other Trojan horse slipped past my defenses. This just turned out to be the night, and poor Jessie the unwitting instrument.

To be honest, I was hardly even aware of Jessie anymore by the time I begged everyone’s forgiveness for leaving early, on grounds of feeling suddenly unwell—an excuse which must only have increased the drama surrounding my failure to appear at work the next morning—or ever again.

I should just have gone home. But I was far too upset to think of sleeping, or even sitting still. So I drove downtown instead, parked my clean, well-maintained car in an all-night garage, and went out to walk the City Center’s empty streets, desperate to conceive of some speedy way to re-inflate my ruined blimp.

I am never likely to forget a single detail of that walk.

It had rained some, earlier, leaving the deserted streets puddled and slick, the air clear and chilly, smelling of wet concrete and asphalt. Here and there between the tower tops a hard-edged star pierced the dozing city’s half-light. The night was silent, undisturbed by so much as a passing car for minutes at a time. The sheen of sodium streetlights, traffic signals, and neon signs reflecting so brightly off of all that wet pavement made the few remaining shadows even more impenetrable.

My suit coat was too light for the weather, and it got colder as the hours passed, but I was in such a state of despair that I hardly noticed. I just walked and walked—trying to outdistance the inescapable consequences of a lifetime’s folly.

The way I saw it then, I had been tricked—not by Brian or Jessie, but by ‘fate’ itself—into encountering myself and my life now, after all those years of hiding from both. Of course, no one had tricked me but me. And here I was, doing it again. The ‘all-that-can-wait’ trick I’d been using for so long had just morphed seamlessly into the ‘it’s-too-late now’ one.

Deep down, I think I’d known for decades what I truly wanted: a few real friends; a wife and children; a handful of adventures—just the normal kind that equip you to grin knowingly at other such adventurers, and receive similar grins in response.

Yet I’d put all this off, again and again, waiting for some more spacious and convenient tomorrow when all my more urgent business had been seen to: the endless streams of email, bill paying, mail-in rebating, and receipt arranging; the acquisition and maintenance of things; the maneuvering for advancement; the house cleaning and grocery shopping for microwave dinners eaten in exhaustion, alone in my tidy house, before an endless train of reality TV shows, watching people even less real than myself live lives more fake than my own. All I’d really wanted was to be someone that someone like Jessie might have wanted, back when someone like Jessie could have wanted him. Why, I wondered miserably, had I never admitted all this to myself before? And why, after hiding from it so carefully for so long, had I suddenly let myself see it all that night?

Though I didn’t know the answers then, they seem clear enough to me now.

I had allowed my walls to crack at last precisely because, having crossed the magic line of fifty, it was finally officially too late to do anything about it, and so there were no longer any fearful obligations incurred by acknowledging my real desires—except, perhaps, despair. But mere despair was entirely safe. It required none of the effort, risk, or courage that desire, hope, or, God forbid, action, might have thrust upon me had I faced any of this sooner.

That night, however, with decades likely left to wait, hopelessly and pointlessly, for some legitimate exit from this impossibly costly, failed experiment in cowardly evasion, I had no idea what I was supposed to do with all the empty, useless years ahead of me. How was I to survive the suddenly inescapable consciousness of all I might have been and done had I just dared to face myself while there was ‘still time?’

It was a far more timely question than I could have guessed, though I had very little time to consider it before I was suddenly distracted by much more immediate trouble.

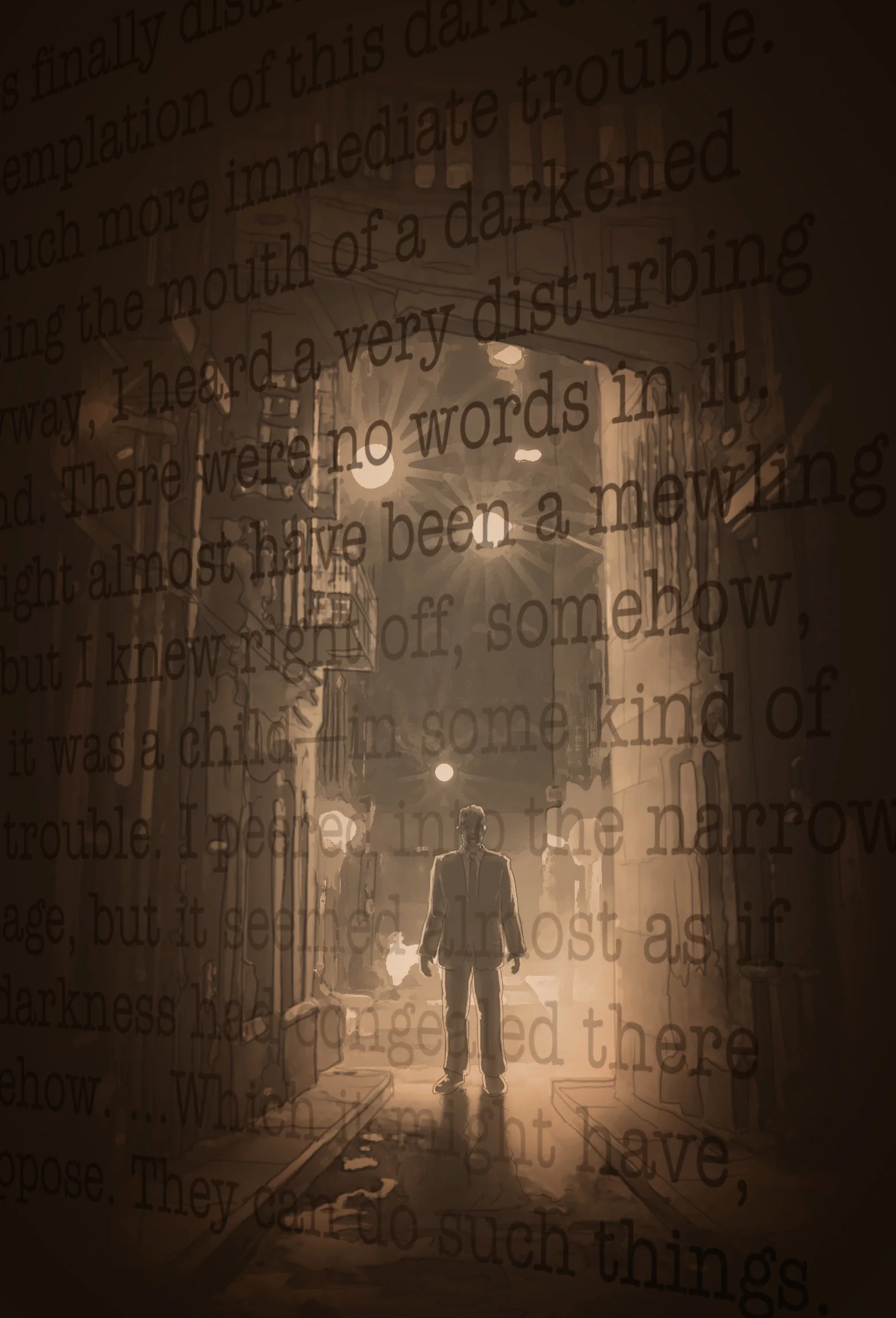

Passing the mouth of a darkened alleyway, I heard a very disturbing sound.

There were no words in it. … It might almost have been a mewling cat, but I knew right off, somehow, that it was a child—in some kind of real trouble.

I peered into the narrow passage, but it seemed almost as if the darkness had congealed there somehow. …Which it might have, I suppose. They can do such things.

“Who’s in there?” I called out.

A high-pitched little squeal, abruptly silenced, left me rigid with alarm.

The violence conveyed in that small, aborted sound was terrifying. But some even deeper instinct must have trumped my fear, because, without really thinking, I rushed stupidly forward, fists absurdly raised, and ran straight into someone much too large.

The darkness thinned then, just enough for me to see what I had hit.

It wore a long gray coat of tattered herringbone, and ragged, sooty pants that reeked of stale sweat and urine and something else I still can’t name, unpleasantly burnt and herbal. Its head was hideously deformed: cranium shrunken, jawbone overgrown, eyes and nose too small, mouth too large and fleshy, opened in a kind of ghastly ‘O.’

Terms like gigantism and elephantiasis sprinted through my vapor-locked brain, but I never once thought troll.

That’s right. Troll.

And while I’m losing you again, let me insist that you have likely seen things every bit as strange, or even stranger. You just didn’t notice. The last time a troll crossed the street in front of your car, you thought, Wow! Look at the size of that guy! And what an awful birth defect! Poor man. The light turned green, and you drove off without a second thought. None of us ever recognizes what we know cannot possibly be there.

They count on that.

But I digress.

One of the creature’s huge hands held a teenage girl up against the alley’s brick and mortar wall, by the throat. Her feet dangled off the ground. Its grip prevented her head from turning, but her terrified eyes slid toward me, begging eloquently.

I wish I could tell you that I yelled, “Unhand that child, you fiend!” and took a swing at it, but no. I just stood gaping up at both of them until, in one swift, fluid motion, the creature dropped the girl, and swung the arm he’d held her with around to club me in the head.

I don’t remember leaving the ground—just bouncing off a dumpster further down the alleyway. Then he came to finish me. It was like being dropped into a threshing combine. I never once regained control of my body, or even thought of trying. Fear and all but an increasingly remote rumor of pain simply vanished into global disbelief accompanied by two calm, clinical thoughts: I made it to fifty, and, I’m not going to live through this.