THE TREE

Sunshine—not the pale, misty kind Piper and I stood in, but clear, bright, beaming sunlight—spilled from inside the tree.

I bent down to peer through a short passage of living wood at an opening just four or five feet farther in, through which I saw tall grass waving under a clear blue sky. A breeze wafted through it, warmer than the air we stood in, redolent of green grass and sunlit leaves, summer flowers, scented wood, and strange ‘spices’ for lack of any better term. Come, that new air seemed to say. All the brightest summer days of youth await you here.

But I couldn’t bring myself to enter without checking once more to be sure there was not some cleverly positioned tunnel hidden just behind the trunk—or that the apparent space beyond this tree wasn’t really just some ‘illusory wall’ detectable only by touch. I turned and made my way along the narrow strip of shoreline to clamber up over the tree’s tangled mound of roots and down its farther side—where I found nothing but open air between me and the ravine’s wooded slopes. Piper waited patiently until I’d walked clear around to rejoin her from the opposite direction. “How?” I could not keep myself from asking.

“We have no more time to waste on such questions,” she said, ducking through the doorway and bidding me to follow. “Just come see. We’ll talk afterward.”

I followed her through the short passage into sunlit, knee-high grass outside another doorway, also carved into a tree—though not the one we’d entered through. This was an immense evergreen with shaggy red bark from which the ‘spicy’ smell I had detected clearly came. It stood at the abrupt edge of an entire forest of such trees bordering a vast, open grassland—all of which I had mere seconds to take in before my attention was seized by what rose into the sky, far beyond us, out above that endless prairie.

“Oh…” I looked up. And up, and up, in awe.

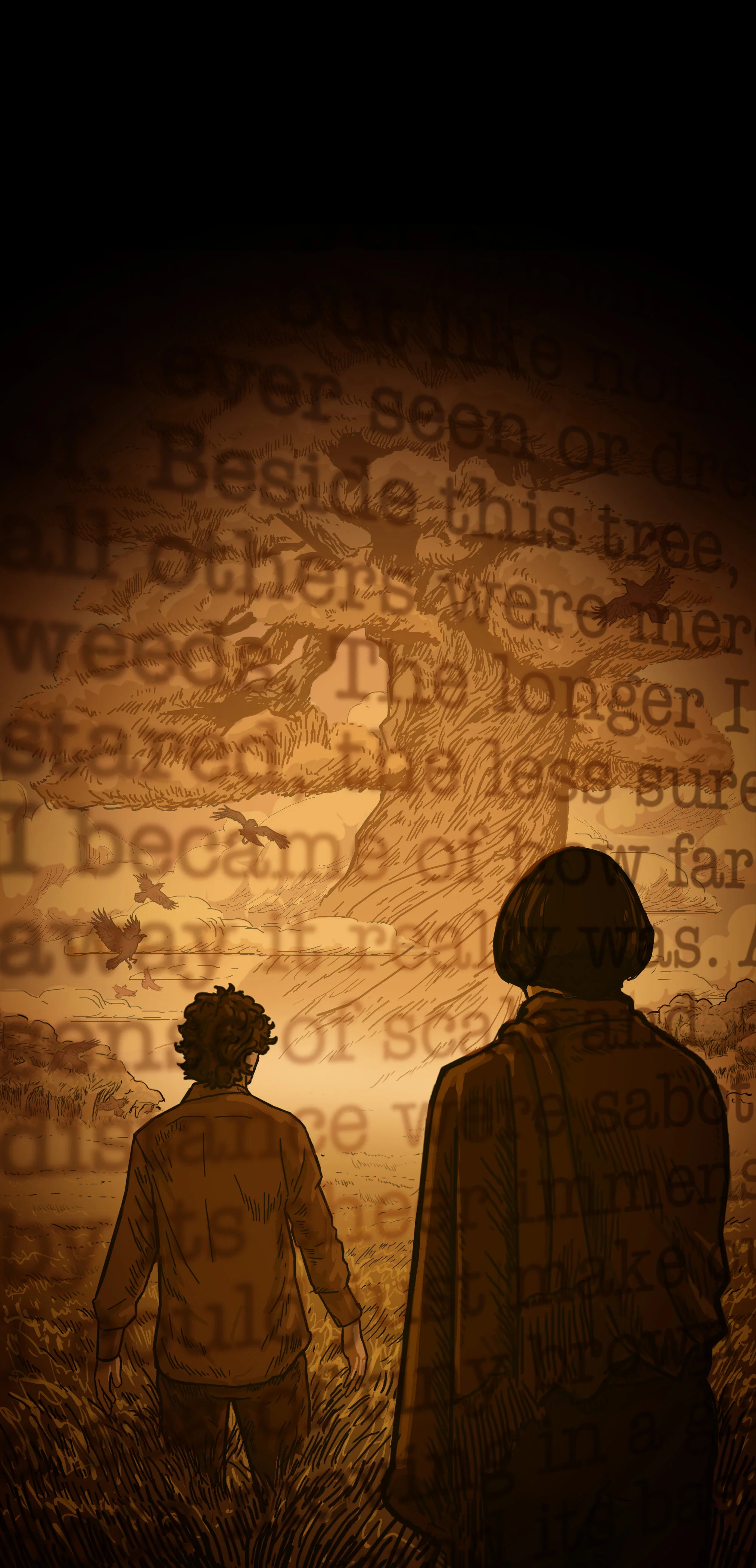

It was yet another tree—but like none I’d ever seen or dreamed of. Beside this tree, all others were mere weeds. The longer I stared, the less sure I became of how far away it really was. All sense of scale and distance were sabotaged by its sheer immensity. I could just make out a sea of tiny brown dots moving in a giant ring around its base, and realized that these were some vast herd of animals, though I couldn’t guess what kind across perhaps the mile or more of distance.

“This is us,” Piper said quietly. “It defines our being, and our lives.”

“…A tree?”

She smiled sadly. “Not just that. Come on.” As she set off into the field, I followed, stumbling repeatedly because it was so hard to take my eyes off of the tree.

Soon, however, my attention was at last drawn downward by increasing movement in the tall grass around our legs. I found the knee-high fronds teeming with butterflies, beetles and grasshoppers, tiny gold and emerald frogs, even plump little birds scattering up and away from our swishing legs, but only ever in the same direction we were heading. The farther we went, the more varied and numerous this understory of scattering companions became: snakes with gleaming, iridescent scales, and lizards large and small slithered among the hopping frogs and birds now, alongside darting mice, moles, and what looked like little squirrels. My stride became a hopping dance as I tried not to step on them, until Piper looked back, and grinned. “They’re far better at avoiding you than you’ll ever be at avoiding them. Just walk straight and steady, Matt. They’ll keep clear of your feet.”

“What are they all doing here?” I asked.

“The same thing we are,” she said over her shoulder, “heading for the Tree.”

“Why?”

“You’ll see.”

As we kept moving, the tree’s huge base became more visible: a vast dome of massive roots that plunged into the ground only to rise again farther across the wind-rippled field, looping up into the air, then down again, and again, like monstrous serpents in a grassy sea. Above this undulating tangle, the tree’s fluted, copper-hued trunk thrust up wider than a house to spread tier above tier of densely verdant branches, each wider than the last, as it soared perhaps a thousand feet into the turquoise sky.

Not much later, I noticed what seemed to be wreaths of smoke rising in broken spirals around and through the vast shelves of foliage. It moved very strangely, though, fanning out one moment, swirling into tight, twisting formations the next, sometimes plunging suddenly into the great leafy bowers, or rising out of them in explosive bursts.

The air around us was growing more and more crowded with birds of every description: larks, finches, chickadees, and hummingbirds, cockatiels, parrots and peacocks, doves and pheasants, nightingales and nuthatches, crows, ravens, geese and gulls, terns and cormorants, owls and hawks and eagles, all fluttering, gliding, soaring past us toward the tree in eerie silence broken only by the rhythmic ruffle of their countless wings; their avian attention too riveted on our shared destination to be spared for chirps, caws or screeches. It took me a while longer to understand that these birds were the wreaths of ‘smoke’ I saw wheeling up and up around the titanic spire in their unimaginable flocks.

Things were growing crowded on the ground as well. The swarm of tiny creatures accompanying us was being joined by larger animals now. Ambling raccoons and prancing foxes, leaping antelope and rabbits, trotting pigs, loping coyotes and shuffling beavers nearly half my height all traveled side by side in similar silence without apparent fear of, or even interest in, me or one another. Like the birds, they seemed to have attention only for the tree. As bears and horses, reindeer, wildebeests, leopards, rhinos, tigers and giraffes, great apes and even elephants appeared among the throng, my alarm grew frantic.

“Is this safe?” I called to Piper, shying one way then another from beasts many times my size, which I had never seen before without a wall of iron bars or plate glass to protect me.

“Injury and death are more than just forbidden here,” Piper called in reply as two wolves trotted past us in the grass. “They are unthinkable. Nothing here is ever harmed—or can be. But it will only get more crowded as we near the Tree, so concentrate on setting down your fear. This is a miracle, of sorts; one you are unlikely to experience again. Enjoy it, Matt.”

Enjoy it? I thought as a cougar nudged past me nonchalantly. I could smell it—fur and musk—hear its quiet, panting growl, feel the silky bristle of its hair against my skin as I snatched my hand away. But it wasted not a glance on me as it flowed forward toward the tree—which towered above us now, all but filling my field of vision, though it seemed still at least a quarter mile off.

I took deeper, slower breaths, and kept my eyes raised to the tree’s lush, lower branches ruffling and swaying in the wind. The stream of birds there was easily discernable now, swirling ever upward like some mammoth, undulating flight of living stairs. The air had become a pungent stew of animal scent, though the smell, I realized, was not at all unpleasant. There was no filth or illness in it—nothing of the cage or farm yard, only the rich incense of unfettered life.

Half an hour into our trek, the beasts around me had become too densely packed to avoid anymore, as the whole vast herd began veering right, pressing Piper and me along into the great gyre circling the tree. Somewhere in this press of hide, fur, scent, and the surf-like susurration of countless breathing animals, everything inside me finally surrendered to Piper’s assurances of safety. With hardly a thought, I steadied myself by throwing my arms across the backs of an oryx to my left, and a lioness to my right. Neither seemed to care, but only pressed further up against me, gently, as if to guard me from the surge around us. Feeling all but dissolved into this river of pure life, I threw both arms across the lioness, and pulled myself onto her back. She hardly slowed as I pressed my face into her fur and wrestled my right leg over her far side before pushing myself upright to look out across the vast sea of backs and heads now moving round and round the tree.

Just ahead, Piper rode an antelope clearly unconcerned about the lioness behind it. She thrust her hand up in a gesture of command, and both our mounts pressed slowly left, veering through the herd now, toward the living wheel’s inner rim. I gazed up at the tree again and couldn’t look away—lost in a unity of kinship, and a consuming sense of my own physical existence. I no longer cared how all of this could fit inside an old, dead tree. I felt no desire at all to understand or question this experience. It didn’t just feel ‘real’ to me now; it felt more real than any experience I’d ever had.

We were underneath the tree’s lowest bows now, and spiraling ever nearer. This close in, I could see heavy clusters of trumpet-shaped blossoms—white and pale yellow at the center, fading to orange edged in plum—dangling from breeze-born rafts of giant, fan-shaped leaves. I was close enough to breathe in their perfume. Watching swarms of creatures climb, swing, and flutter in those branches, an urgent yearning germinated in my stomach, spreading quickly through my chest and limbs. “Can we climb it too?” I called to Piper, who was staring up into the tree as well.

“Not today,” she answered, sadly.

Her verdict filled me with disappointment. I had come to understand by now, along with every other creature I could see, it seemed, that all my heart’s most urgent desires waited up there somewhere, farther on, beckoning us all to climb, and climb, and climb. I longed, mind and body, to embrace that invitation. “Why not?” I moaned.

“The world is not through with us,” she sighed.

At that moment, our mounts broke free of the great wheel of animals, into a nearly empty ring of shady meadow around the tree’s cliff-face of a trunk. The animals we rode laid down then, clearly bidding us to dismount. When we’d done so, the antelope sprang up and gamboled a short distance before pausing to lean down and crop the rich, moist grass. My lioness loped off toward the tree, flung herself onto its trunk, and started clawing higher, going where I was not allowed to, for some reason. I watched enviously as it vanished up into the foliage as Piper walked toward the wall of polished, copper-colored bark, which stretched off in both directions, hardly seeming to curve. I followed suit, hungry just to touch the tree that I was not permitted yet to climb. The antelope raised its head to look at me with twitching ears, but made no move to flee as I passed by.

Dragonflies of a dozen colors thrummed around me, all heading farther up into the tree. Jewel-toned birds peered down at us, twittering and squawking now, among its rustling leaves. Countless other creatures stirred there too: lemurs, leopards, hanging flocks of fruit bats, sloths and green iguanas. A great cloud of sapphire butterflies, each larger than my hand, engulfed me in an iridescent storm of gleaming wings on their way to press themselves against the ruddy trunk like a fluttering carpet of twilight sky. Each step closer to the tree revealed another, finer layer of teeming life. Orb-woven spider webs belled in the breeze like gossamer sails of glinting rainbow. Streams of insects crawled up its armored girth: iridescent beetles, long-legged walking sticks and crickets, bright blue centipedes, herds of ladybugs swarming around hand-sized tree snails gliding ever higher, their shells bedecked in swirling stripes of black and yellow, brown, orange and white. Every living thing here seemed intent on moving higher up into the tree.

As she reached the trunk, Piper raised a hand to press her palm against its smooth, cool surface. I followed her example, and, a moment later, pressed my forehead to the tree as well. Why can’t I climb you too, I begged it silently.

“What would you hope to find up there?” I heard Piper murmur in reply.

I turned to find her still just gazing at the tree.

“Can you hear my thoughts?” I asked aloud.

“I don’t need to. Everyone asks the same question when they come here the first time.”

“Do all of you come here then?” I asked, feeling something jealous twist beneath my ribs.

She nodded. “Every child of parents who know that they are Memphir Zharro is brought through some portal to some version of this place as soon as we are old enough to speak and understand, so that we may know, right from the start, who and what we truly are, and what matters most in a world so full of chaos and seduction.” She turned to me at last, with a pale, sympathetic smile. “I have never heard of any child who did not beg to climb, and mourn the answer everyone is given, just as you do now.”

“No one is allowed to climb it?” I asked, astonished, and appalled. “Ever?”

“We are taught,” she said softly, “that each of us will be allowed to climb the Tree as soon as we have learned, at our very core, what it is we climb to find.” Her sympathetic smile returned. “So, Matt, what is it you would hope to find up there?”

The answer seemed laughably obvious, at first. But when I tried to speak it, I found no adequate words. I thought, life, but knew she’d ask me what that meant, and knew I couldn’t say, precisely. I thought love, and truth, and even joy, but just as quickly saw that each of those was just an abstract placeholder for something I could not sufficiently define—even for myself.

Piper nodded knowingly. “I’ve heard it said, by wiser heads than most, that when one finds the real answer to this question—then, and only then does the world release us to come climb the Tree at last.”

“What does that mean?” I asked uncomfortably. “The world releases you…how?”

She gazed at me in silence, then back at the veritable sea of animals we had come here through. “There used to be far fewer, I am told; even just a couple centuries ago. Now… You see how many of them come to climb the Tree.” She no longer smiled. There was only sadness in her face now—or something worse. Grief, perhaps, or fear.

“Are you saying all these animals…are dead?” I asked.

“That depends,” she said. “The word seems to mean something very different to most of your kind than it does to mine. I’m just saying that the world we know is through with them. And, unlike your kind, or mine, they know, almost from the start, what they seek up in this Tree, and so find their way here much more quickly.” She looked out again towards the endless gyre of creatures. “But not that long ago, I’m told, these animals were sparse enough for one to wander past with ease. Not like this. I saw no people but ourselves in the herd today either.” She looked up into the branches. “Nor have I seen one climbing since we came. That worries me most of all.” She drew a long, deep breath, and shrugged. “This is just a mirror of the Tree itself, of course. But still, what it reflects cannot be…easily dismissed.” She shook her head and looked away.

“Just a mirror?” Something sharper leapt inside me: distress, grief, maybe even anger, slicing through the rapture this place had inspired. “This isn’t real then?”

She threw her head back and groaned. “Again? This…frame you’re trapped in is never going to let you go, is it.”

“Well…what did you mean by—”

“Listen to me,” she cut in fiercely. “Just…for once, set all your bent assumptions down and try to really hear what I keep telling you, okay?”

“All right,” I said. “I’m listening.”

She folded her arms, and cocked her head, clearly unconvinced.

“Really!” I insisted. “I’m listening!”

“Fine. Then tell me; every real thing that’s ever happened to you—where did all that really happen?”

“What?”

“Where has all this real life you care so much about actually happened, Matthew?”

I had no idea what the question meant. “…In…the real world…I guess?”

“No, I mean where does it happen to you?”

“I…don’t understand the question.”

“Well, that’s a step in the right direction. Let’s refine the question then. Where do you actually see ‘real’ things?”

I hunched my shoulders and turned my hands out in a helpless gesture. “…All around me…if…I’m not hallucinating?”

She looked down wearily, then up at me again, and pointed at the side of her own head. “You see them here, Matt; in your brain. That is the only place that any real thing you have ever experienced—with any of your physical senses—actually ever happened to you.”

“O…kay. I see where you’re going, but when my brain sees something real, it’s because something really happened—out there. When you just project things at my brain, nothing really happened—out there—did it?”

She stared at me and sighed. “This is why your kind and mine will never understand each other.” She looked back out at the endless tide of animals, up at the leafy ceiling high above us, and, finally, back at me. “Whatever may be happening ‘out there,’ Matt, neither you nor I have ever experienced it, nor ever will. What happens out there is translated into interpretive impulse data by receptors in your fingers, your eyes, your nose or ears or tongue or skin. That abstracted data is then translated—again—within your brain—which constructs ‘experience’ of sight, sound, taste, touch, smell, and a myriad of subtler senses, half of which your kind has hardly even noticed yet, much less invented names for. You call these inventions of your brain ‘reality,’ but nothing beyond those constructs has ever happened to you at all, Matt. Your mental constructs, or ours; how different are they, really? Without your brain’s manufactured illusions, nothing ‘out there’ happens to you at all. Once you finally get that—really get it—you too will have to come up with a whole new set of definitions for what ‘real’ really means—just as we have. Then, and only then, might you stop hammering at these useless questions about what is ‘real,’ and ‘how it’s done,’ and start learning how to live among us.”

“So…where does that leave this?” I gestured at the tree I’d been so desperate to climb just moments earlier, feeling more a fool than ever.

Piper gazed sadly at me. “A few moments ago, I thought you finally understood, or were beginning to, at least,” she said at last. “So, here’s one final fun fact, before we go. Your unimpeachable ‘reality machine’ up there discards all kinds of real data—all the time—if meaning hasn’t been assigned to it. Did you know that? Turns out even your kind thinks that meaning is as real as data sometimes.” She drew a long, shuddering breath, and shrugged as if the entire subject were of no real importance. “Unfortunately, out there in the real world, you have to be at dinner soon, so feel free to take one last look around, because we really need to get you back now.”

I was unable to decide whether I should feel ashamed or indignant. The only clear feeling I had was loss. I turned to look around me, oddly desperate to see everything I could, whether all of this was ‘real’ or not, and found a bobbing twig suspended just above my head, on which an enormous katydid of lime-peel green with magenta stripes crawled carefully along a leaf edge. Black beads at the centers of its bulbous, chartreuse eyes pointed down at me as if to ask, Why aren’t you climbing too?

I raised a finger to touch it, and its long, swooping antenna began to dance about, tentatively brushing at my skin. Slowly, cautiously, the creature lifted first one attenuated leg, and then another, to step onto my hand. I felt each tiny foot touch down, even tinier hooks snagging purchase on my skin before the next foot moved.

It really is…so real, I thought, that quickly lost in awe again. How can all this seem so real? “Will I…ever get to come back?” I asked aloud, demoralized to think I’d failed this test too, whatever it had been.

“Does it matter?” she replied. “Why waste concern on things that aren’t real?”

I teased the katydid gently back onto its perch, and turned to scowl at Piper. “I’ve never claimed to be right—about anything here,” I said, both irritated and embarrassed. “I can handle being wrong. I’m wrong most of the time these days. I have no idea what to believe about anything now. But I just met you people this morning! I’ll need more than a day or two to sort out a whole world turned upside down. So have a little mercy, will you?” She just looked unhappier with each word I said, until it suddenly occurred to me to wonder whether it had really just been me she’d been upset with. “All of this…is beautiful,” I said, gesturing around us. “No matter what it is, or how it works…I’ve felt things here I’ve…never felt before. I won’t forget this, ever. Or stop thinking about…any of it. Not for quite a while, at least. I haven’t forgotten this is sacred to you, and I never meant to criticize…” I gave up and fell silent, sure that I could only make things worse from here.

She was looking at the ground now—no longer mad at me, it seemed, if she ever really had been. I chewed my lower lip, wondering just how badly I’d misread things.

“I too…leave with much to think about,” she said, still looking down. “Perhaps it wasn’t me who led you here after all. Maybe you brought me to hear what the Tree had to say. I keep treating you…so badly.” She looked up at me, her eyes moist with unshed tears. “I don’t understand that either. You’ve done nothing wrong at all—here or anywhere since you arrived. But, we really have to go. …I’m sorry.” She turned, swiping at her eyes, and started heading toward the herd still trampling its endless course around us and the Tree.