THEM

After venting my frustration by shouting curses and throwing chunks of broken siding around, I’d stared dejectedly for a while at the pile of construction clutter where my bags had been, and finally thought, I guess this is where I sleep now. Having propped a sturdy pile of corrugated metal scraps together against the building, I’d crawled beneath them with some cardboard to wrap up in, and gotten just warm enough to fall fitfully unconscious.

Only to be awakened at the crack of dawn by someone stomping on my metal bower.

I just managed to scramble out before it collapsed, and turned to find a startled Latino construction worker in an orange safety vest and yellow hardhat, staring at me from atop the pile. His surprise changed rapidly to irritation as he said something impatient in Spanish, and waved me away. I shrugged in resentful apology, and headed toward the street, thinking people sure started working awfully damn early down here.

As the city stirred to life around me, I wandered down dawn-gilded streets, scratching at bug bites I’d acquired overnight. I felt stiff and cotton-headed, unsurprisingly, but limbered up with surprising speed…because, of course…I was a boy again. The fact brought me to a complete halt there on the sidewalk. A night’s sleep—however poor—had left my mind considerably clearer than it had been since…well, before ‘the miracle’—or whatever this was—and the enormous impossibility of my condition seized me all over again, at some even deeper and more lucid level than it yet had. How? How can this be? At that moment, this question mattered even more to me than how I would survive.

I sat down with my back to the wall of a still-closed shop front as the whole cascade of potential explanations coursed through my mind all over again. Was I actually in a coma somewhere—or, perhaps, just driven mad by trauma—and hallucinating? No. By now, I knew, in my very body, that this wasn’t just some kind of dream. It had already gone on far too long, in too perfect detail, too coherently even, in its impossible way. Some…new super secret medical technology then? Radical gene therapy, or…quantum…reconstructive…what? I shook my head again. Not administered overnight by some bag-lady in an alleyway, surely.

Could I actually be dead then, and…the afterlife was…this? I looked around—at all the dirt and rust and gritty concrete; breathing the exhaust-scented air and listening to the percussive susurration of urban traffic, machines, and people already filling the air around me; watching wind-blown trash skitter between the whizzing cars across streets crazed with asphalt seams and iridescent oil sheen; gazing up at runnels of bird shit festooning architectural cornices—and shook my head. If there was an afterlife, it just could not be so little different from the living world, could it? What would be the point? Why not just keep living where we’d started? …And, again, I just didn’t feel dead.

So…what then?

There was only one person I could think of who might be able to tell me. And I had to find her—somehow. She’d been right. This had been the world’s stupidest wish. I shook my head—shoving the whole useless sea of questions away. There had clearly been some way to do this to me, so there had to be some way to undo it.

If there were any clues to find, they would be back in that alleyway. Who knew, maybe she’d even left a note or something. I mean, really, would she have done this to me—in gratitude for her daughter’s life—and then just left me there to cope with what she’d obviously known was going to be a very problematic future? How grateful would that have been? A kind of hope began to kindle in my gut—along with increasingly ravenous hunger. The appetite of a teenage boy was clearly going to be very inconvenient given my current circumstances. I needed a bathroom too. A restaurant would meet both needs—if I could find money to buy a meal there. Fingering the precious ATM card still in my pocket, I stood up and went in search of a cash machine.

But, as I walked, my stubborn mind went right back to sorting practicalities. What was I going to do if she hadn’t left her business card in that alleyway? Assuming I did still manage to find her somehow—in this giant city—with no real freedom even to ask for anyone’s help in the search—and she did agree to change me back—how long might all that take? Would my former life even be there by the time I got this sorted out? My job? My car? My condo?

The condo itself had been paid off in full for several years by then. And the man I’d been had long since arranged for all his bills to be auto-paid, of course. There was a lot of money in my accounts after so many years of careful saving with so little ‘life’ outside of work. So utilities and insurance and condo association fees and all the rest of that now-irrelevant infrastructure would go right on being taken care of for some time, I supposed. Even if it took months to get all this resolved, then, I’d likely have a home to go back to.

If only I dared go back to it now, I thought. I’d left things there that would be very useful: more money, extra credit cards, my laptop. But I’d be stupid to go back there anytime too soon. The police had already been there looking for me—or rather, for him. They’d still be watching the place. Too big a risk for the juvenile fugitive I’d become.

My car would be towed before long too—if it hadn’t been already, but I could likely get it back. Abandoned vehicles were impounded somewhere, weren’t they? For a while at least—until the owners suddenly reappeared…with what story, exactly, to explain their lengthy and alarming absence? What was I going to tell people—like those police, and my building manager, and my boss and colleagues? Assuming I still had a job by then.

I shoved this crowd of pointless questions away too—more forcefully than before. First things first—and right now that meant food.

I had no idea where to find a branch of my own bank nearby, and no phone anymore to solve that problem for me. But my stomach was too impatient to look farther than the first bank I came to, even if that meant paying a transaction fee. I stuck my card into the ATM, selected ‘English,’ typed my PIN, and stared in disbelief as the machine shut down again without returning either cash or card. I stamped the pavement, hammered the keypad with my fists, and shouted threats. A week ago I’d been a comfortably employed, well-respected, fifty-year-old administrator. Two nights ago I’d been—well, semi-psychotic perhaps—but I had still possessed a bed to sleep in, a well-stocked pantry, and a comforting array of financial resources. Now I was a very hungry street urchin without access to anything but air and sunlight. What had I done to deserve the theft of my last financial lifeline now—by a mindless machine?

A very disturbing answer occurred to me.

Had my disappearance already been reported to ‘the system’?

Of course it had. There’d been officers at my home the day before. And who knew how or where last night’s mugger had since tried to use my credit card?

I could just imagine the messages being left by now on my stolen cell phone, about suspicious activity on my accounts and the new credit, debit, and ATM cards which should arrive within several business days. We apologize for any inconvenience…

Were the police now actively searching for that kid who’d run off from a hospital with the missing man’s suit and keys and wallet? All that I.D. had vanished again with me, of course, but had the EMT or those cops parked behind the ambulance written down his name and address before I’d awakened? Was that what had sent those cops to my home?

I looked nervously around, wondering who might have seen me beating on the ATM, then up at the enclosure’s camera portal. Crap. I turned and ran like hell—again.

As I fled, my mind filled with thoughts of the nameless woman who had caused all this, ‘in thanks.’ As if! Screw breakfast. Anger drove my youthful legs right back to where she’d done this to me.

By morning light, the alleyway was neither scary nor at all remarkable. I strode inside and looked around, irrationally hoping to find her sitting there again, waiting to apologize. …Or to ask me if I’d learned my lesson yet.

Was that what all this was about? Was I being punished for not listening when she’d told me what a stupid wish I’d made?

The thought made me even angrier.

I vented some of that fury by peeing against the dumpster she’d been sitting on. After that run, my bladder wasn’t going to wait any longer, and right now, it seemed a fitting gesture. When I’d zipped up again, I stomped around some more, looking for clues—that so clearly weren’t there. She really had just left me here—like this—to figure it out alone.

“You knew!” I shouted. “You knew and did this anyway—without a goddamn word to warn me it could happen! What kind of lesson is that? What kind of favor?!”

I lunged at the dumpster she’d been sitting on again, and kicked it—over and over, venting more of the rage and madness I’d been storing up. I was lucky not to break my foot.

“Why?” I yelled up at the vacant windows, hoping she was living behind one of them, with the daughter I had saved, listening to me now. No one answered me, of course, and as the silence stretched, my pointless tantrum began to crumble. “You were right, okay? It was a bad wish, but I’m sorry! …I’m sorry now. Okay?”

As my sense of impotence grew, my anger collapsed entirely. “Change me back,” I begged of whoever might be listening behind those indifferent windows. “Please. …Please …”

“Please, shut up!” urged a harshly whispered voice behind me. “Or do you want more of Cullen’s attention?”

I whirled to find a teenage girl at the alley’s mouth, peering tensely around the corner at me, as if afraid of being seen. An ugly bruise ran down one cheek from underneath her bobbed off, blue-black hair. Her large, dark eyes held more irritation now than fear, but I could hardly fail to recognize the girl I’d saved that night.

“You!” I gasped. “Oh, thank God!” I nearly wept. “I have to see your mo–”

“Shhhhhh!” she hissed. “They’ll hear you, idiot!” She nodded me crossly toward the street, then vanished back around the corner.

Desperate not to lose her, I rushed to follow, but rounded the alley entrance to find her already well down the street, still beckoning me to follow as she ran.

She ran so fast that I thought at first she was trying to lose me. But when I finally caught up two blocks later, she just looked over without slowing, and exclaimed, “I cannot believe my mother wasted so much on such a moron! What were you trying to do back there?”

“Can’t we—stop yet?” I gasped.

“No,” she said, seeming hardly out of breath at all. “I’ll tell you when it’s safe. Until then just be quiet and keep up.”

We ran another block toward the still-rising sun, then three blocks north, two more west, and turned south again, as I struggled ever harder to keep pace.

“We’re—running in—a circle,” I gasped.

“What did I say?” she growled. “Shut up and keep up.”

Just staying beside her took all the breath and strength I had. A block later we turned left again—straight into a dead-end alley. She just kept running toward a brick wall not fifty feet in front of us. I looked behind, afraid of being trapped here by whomever we were running from, but I saw no one in pursuit. Before I could turn back, she grabbed my arm and yanked me right off my feet. Too shocked to yell, I plunged headlong toward a blank brick wall just to our left, shoving out my arms against the impact.

But there was none.

Instead, I skinned my hands and knees against a cement floor—inside a darkened basement—then curled into a ball, pressing my abraded palms against my stomach, and biting my lower lip against the pain.

I hadn’t even seen a door there, and when I looked again, I still just saw a wall where I was sure we’d fallen through. “Ouch!” I gasped, flapping my stinging hands. “Where are we?” I groaned, batting feebly at my aching knees. “Ouch, ouch, ouch!”

“Sorry,” she said sullenly, reaching down to offer me a hand. “I didn’t think you’d fall.”

Grasping her hand—or anything else—was nothing I wished to try yet. I rolled away and got up on my own. “What the hell is going on?” I demanded, hugging my still-stinging palms against my sides. “How did we get in here? Whose basement is this?”

“Ours,” she said. “And I’ll catch hell for that too, but I can’t see what choice I had after all that racket you put up at Anselm’s very doorstep.”

“Anselm who?” I asked impatiently. “Is that who we were running from, ’cause I didn’t see anyone behind us at all.”

“Like you didn’t see the door?” She nodded at the wall behind her with a smirk.

“What door?” I shot back. “There’s no door there!”

“You fell through the wall then?” she countered dryly. “Your head must be even harder than I thought. Seems like either it or you should be more damaged though, doesn’t it?”

Unable to formulate any adequate reply, I stifled my anger. What really mattered was getting this girl to take me to her mother. If that meant humoring her, so be it. “All right,” I said. “So, who are all these people I can’t see?”

“Anselm’s little tattlers. They’re likely all asleep this time of day, but if any of them saw us there, both our asses are in embers now.”

“And what has Anselm got to do with either of our asses?” I pressed.

“Anselm owns the creature you found me with the other night.”

“Which I was just moronic enough to distract for you,” I replied, feeling suddenly more sad than angry as I recalled how much it had meant to think I’d sold my worthless life to save a child. …This selfish, scornful child. “You don’t care at all what that cost me, do you?” I said wearily. “You’re right. I am a moron.”

To my surprise, the mockery on her face began to melt. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m being horrible.” She looked down awkwardly. “I’m…more ashamed than you can imagine—about what I’ve cost everyone.”

This left me nonplussed. “Everyone…who?”

“You,” she said bleakly, “my mother. Our entire faction.”

“Faction…of what?” Just what had I stumbled into here, I wondered with a whole new variety of alarm.

She studied me, then turned away in apparent resignation. “My mother gave you much more than she had any right to, I’m afraid. But my debt is even greater, and all still unpaid. If explanations are what you wish, I suppose you’re owed that much.”

At the mere mention of the ‘w’ word, every hair on my arms and neck stood up. “I’m not wishing anything. Not this time. Let’s get that clear, straight off.”

This drew a grim smile from her. “I didn’t mean it that way. Answering your questions won’t hurt anyone except me, and that’s not your problem.”

“No.” I gestured at my adolescent body. “This is. Can it be undone?”

She looked helpless. “I…don’t know.”

“Listen,” I said, “can you just take me to your mother?”

“You’ve got to stop looking for her!” She was begging now. “She absolutely cannot be seen with you again. And your own safety may depend just as much on steering clear of us.”

“Us who?” I asked again.

She sighed, gazing at the ceiling as if I were too exasperating an inconvenience to deal with.

“That’s a ‘no’ then?” I asked unhappily. This girl knew exactly where the one person who could help me was, and she wasn’t going to take me there. Well, I hadn’t really expected, even now, that all wishes were so easily granted—especially those I meant to make. The world had not changed that much, apparently. “Can I at least know how this was done then? And why?”

“There are better places for such a lengthy conversation,” she said stiffly. “Come on.” She headed for a corner of the basement lost in shadows. “I need some breakfast. Are you hungry?”

Magic words if ever I’d heard any. I hurried after her again only to halt beside her in front of another brick wall devoid of any feature but seepage stains—that is, until she reached to grab a round, brass doorknob that simply hadn’t been there before she laid her hand on it. She pulled open the heavy, wooden door suddenly attached to it, and, like the bellman at some swank hotel, waved me toward it with a flourish.

But I just stood there, gaping, as goose bumps rose on every inch of me—not only because there was a doorway now where none had been before, but because I was as suddenly aware that I had seen that doorway very clearly all along—just as I had seen the one behind me. …From the very start. …I simply hadn’t had permission, somehow, to admit it—even to myself—until she’d touched it.

I turned to look behind me at the wall we’d fallen through, and there it was, just as I had known but refused to know it had been all this time. Another wooden door, in peeling paint of forest green, right where we had plunged in from the alleyway.

“Did you …are you messing with my mind somehow?” I asked, barely above a whisper.

“No! It’s just…” She trailed off, looking contrite. “I don’t know how to explain it to you. Our kind can… I didn’t mean to scare you.”

“Which time?” I asked palely. I looked down at my body, half expecting to find that it had never really been changed either.

“That’s real, I’m afraid,” she said, seeming to perceive my thought. “Nothing like the doors.” She waved me once again, less grandly, toward the threshold she’d just opened. “First, some food. Then I’ll try to answer your questions. The ones I can, at least.”

Beyond the impossible doorway was a dim, wooden stairwell. I followed her up it in a daze, trying to parse what I had just experienced. You might think I’d have gotten past the concept of ‘impossible’ by then, but it took me quite a while longer, actually, to stop reeling inside each time another of my ‘empirical’ assumptions about the bedrock laws of reality was casually sidestepped by these people. Some part of me still clung desperately to the conviction that at least some of what we’ve all been taught in school must still be reliable… This was to be a particularly difficult morning in that regard. Invisible doors were just a modest start.

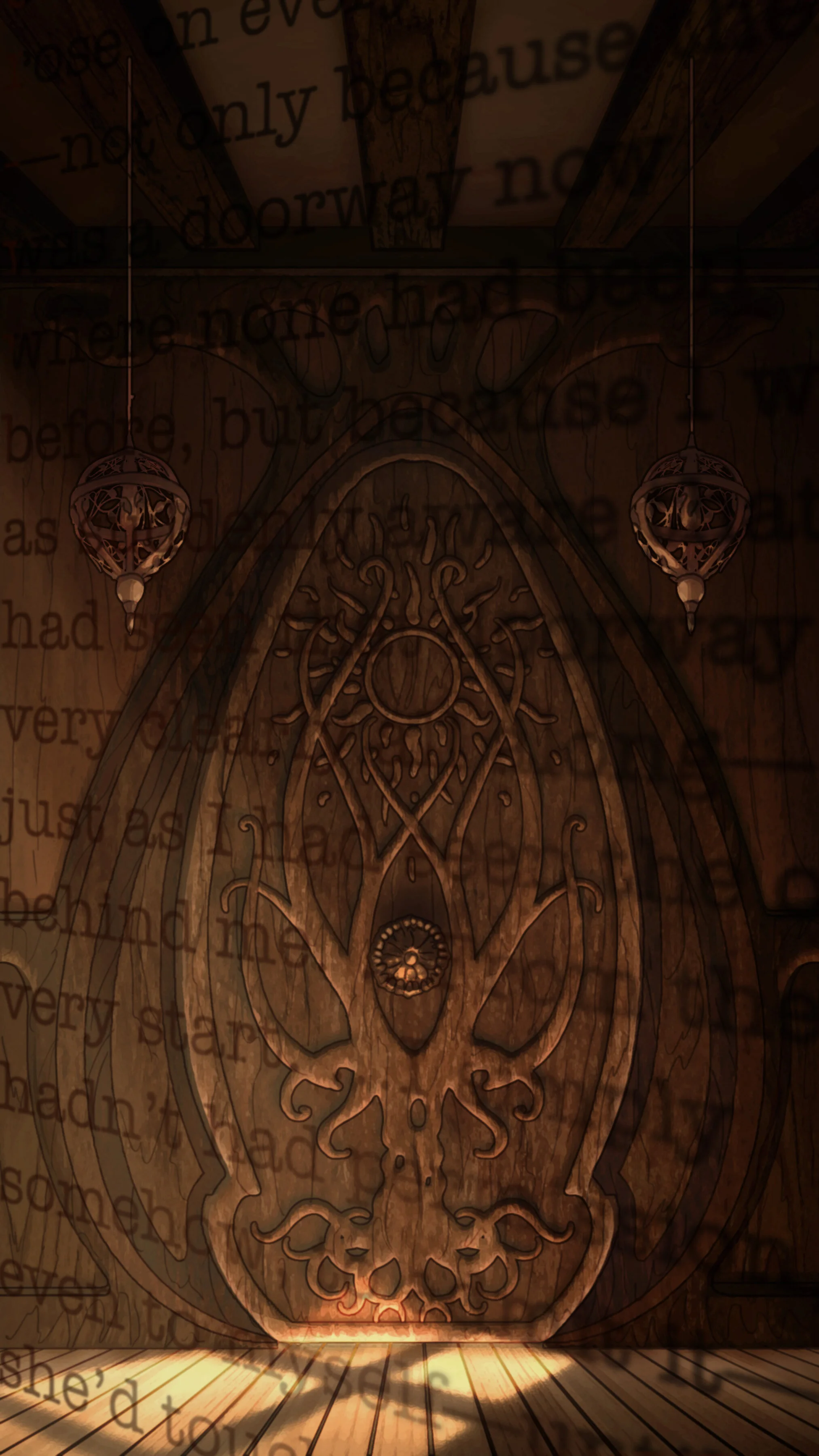

The passage we ascended was lit by small, yellow milk-glass windows placed at oddly varying heights, so that we moved from shadow to shadow through sporadic pools of soft amber light. The wood-slat walls were dark with age, and framed in stout, rough-hewn beams. The wooden steps squeaked almost musically under our weight, producing a strange sort of fugue as we progressed. It seemed a very old building. One of the oldest in the city, I’d have guessed, though I could not recall seeing evidence of any such antiquity from outside. The air smelled like cedar sawdust scented with Danish pastry. The stairwell bent and turned at increasingly irregular intervals until it became difficult to imagine how it might fit into any conceivable floor plan, or even exactly how many stories we had risen. I didn’t think it had been more than three or four before the passage ended on a small landing, at an elaborate, weirdly pear-shaped doorway of highly finished wood, on which the image of a tree, heavily stylized root ball, trunk, and branchy crown, was meticulously carved.

“Welcome, Matthew,” the girl said solemnly, pushing the door open, and standing aside to let me enter first. “I’m called Piper, by the way.”

“How do you know my name?” I was quite sure I hadn’t told her.

She looked abashed. “I’ve been…following you since you turned up again last night. It’s what I’ve heard you call yourself.”

Since last night? I thought. And let me sleep in a pile of rubble? What strange ideas of gratitude you people have.

“Though…Matthew’s not your real name, is it?” she asked.

“And how would you know that?” I asked crossly.

“What’s your last name?”

I had no answer. I still had not invented one.

“That’s how,” she said. “You introduced yourself to at least three people last night, yet never gave them more than your first name. That’s not how your kind does things—when they’re being truthful, anyway.”

“I’m not being truthful?” I nearly screeched. “You spied on me all night, lifting not a finger to help when I was being robbed, and—”

“It wasn’t meant as criticism!” she cut in. “I just wanted to be sure. It’s best to conceal your true name, actually—especially from our kind.”

“Our kind?” I asked. “You keep saying that. What does that mean?”

She looked at me as if I’d asked which way was up. “Have you really still not figured out yet that we’re different?”

“Well… sure, but… You’re not saying you’re not human…are you?”

“Oh, we’re both human,” she said. “Like beagles and wolves are both dogs.”

I stood blinking at her. “I take it your kind are the wolves?”

Her gaze rolled toward the ceiling. “The beagle is a very noble animal,” she said with exaggerated patience. “And our rules of hospitality require me to let you enter first here, so could you please just go inside, so that I can go in too and start making us some food?”

“Should a beagle let a wolf make us some food?” I asked.

Her answering glare sent me quickly through the door, desperately hoping her ‘welcome’ had not been that of the spider to the fly.